Table of contents

Understanding Inflammaging: The Hidden Driver of Premature Aging and Chronic Disease

Zombie Cells: The Cellular Undead Fueling Inflammatory Aging

The Inflammation-Disease Connection: Mapping the Pathways to Chronic Illness

Astaxanthin: Nature's Most Potent Anti-Inflammatory and Longevity Compound

The Unique Molecular Structure: Why Astaxanthin Outperforms Other Antioxidants

Mechanisms of Anti-Inflammatory Action: How Astaxanthin Breaks the Inflammation Cycle

Cellular Protection and Longevity Pathways

Astaxanthin's Targeted Benefits for Age-Related Health Challenges

Clinical Evidence and Real-World Applications

Dosage, Timing, and Optimization Strategies

Practical Implementation: Integrating Astaxanthin into Your Longevity Protocol

Emma Hanegraef

Emma holds a MSc in Cellular and Genetic Engineering and has been passionate about the science behind skincare and health since the age of 12. As an experienced formulator, she translates complex scientific concepts into accessible knowledge, helping you make informed choices about your formulas.

How Astaxanthin Combats Inflammaging and Extends Healthspan Through Cellular Protection

Understanding Inflammaging: The Hidden Driver of Premature Aging and Chronic Disease

Inflammation is your body's first line of defense. It's how you fight infections, repair damage, and adapt to stress. But when this protective response never really turns off, it becomes something else entirely-chronic, low-grade inflammation that silently damages tissues over time. Scientists now call this process inflammaging.

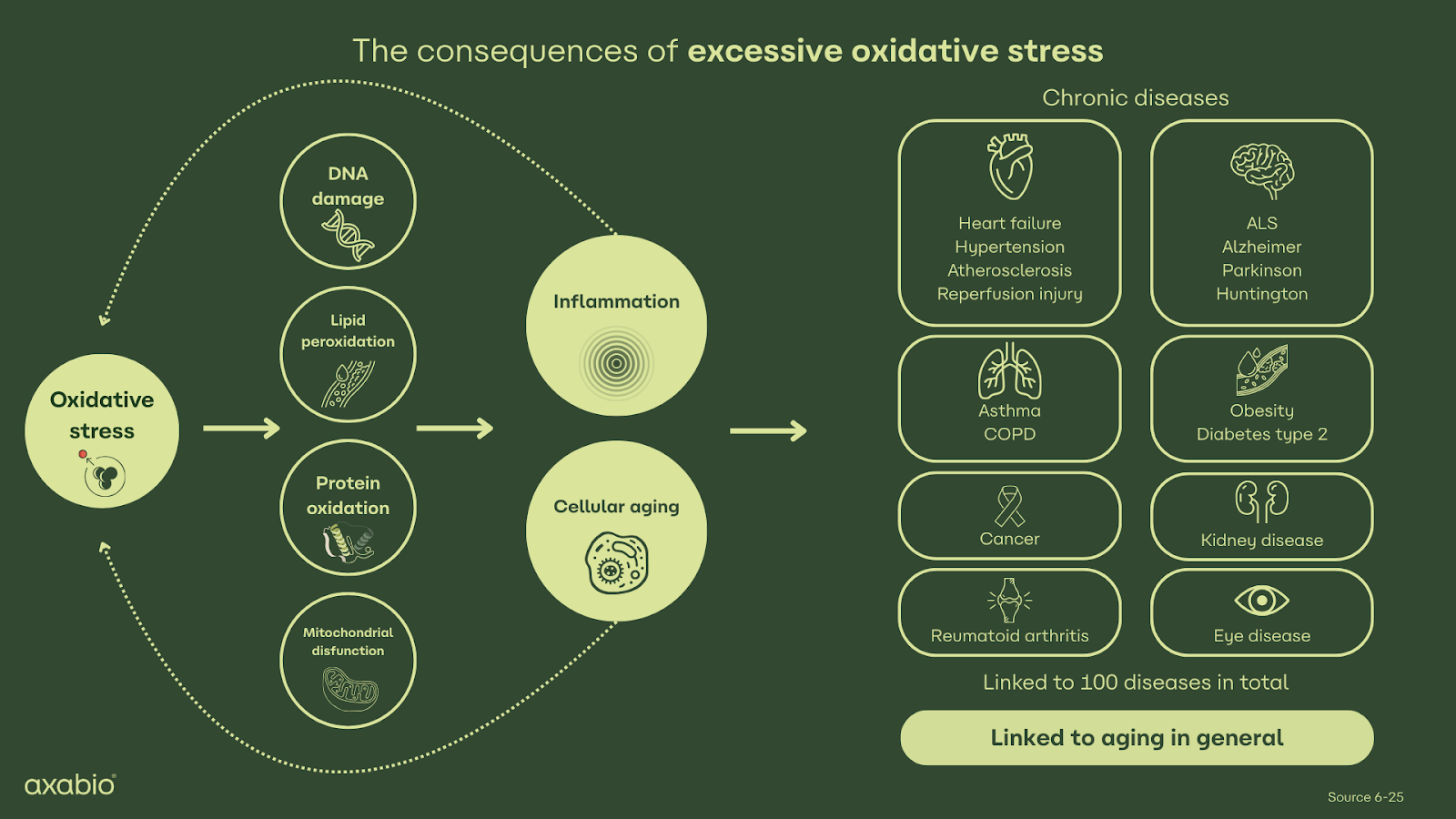

Unlike acute inflammation, which is short-lived and beneficial, inflammaging acts like a smoldering fire. It doesn't cause immediate symptoms, but it steadily accelerates the development of cardiovascular disease, neurodegeneration, diabetes, and even cancer (Franceschi et al., 2018). The good news? By understanding the underlying drivers of inflammaging, we can start looking at active ingredients like astaxanthin to interrupt this process at its root.

The Science Behind Inflammaging and Its Impact on Longevity

Inflammaging has been described as one of the most consistent predictors of biological age-often more reliable than chronological years. Elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, and CRP are strongly correlated with frailty, reduced immune competence, and shorter healthspan (Ferrucci & Fabbri, 2018).

What makes inflammaging so damaging is its systemic nature: it's not localized to one organ, but spreads across the body, disrupting tissues and accelerating wear and tear at a cellular level. Over decades, this silent inflammation erodes resilience, leaving the body more vulnerable to chronic disease.

Defining Inflammaging: When Acute Protection Becomes Chronic Destruction

Acute inflammation is short-lived and essential. You cut your finger, and within hours, immune cells rush in, repair the wound, and leave. Inflammaging, however, is like leaving the faucet slightly open-it constantly leaks inflammatory mediators into your system.

This shift from beneficial to harmful arises from multiple triggers: immunosenescence (the aging of immune cells), accumulation of damaged proteins, mitochondrial dysfunction, and the persistent activity of senescent or "zombie" cells. Together, these factors tip the scale from protection to chronic destruction (Fulop et al., 2017).

The Molecular Cascade: How Persistent Inflammation Accelerates Cellular Aging

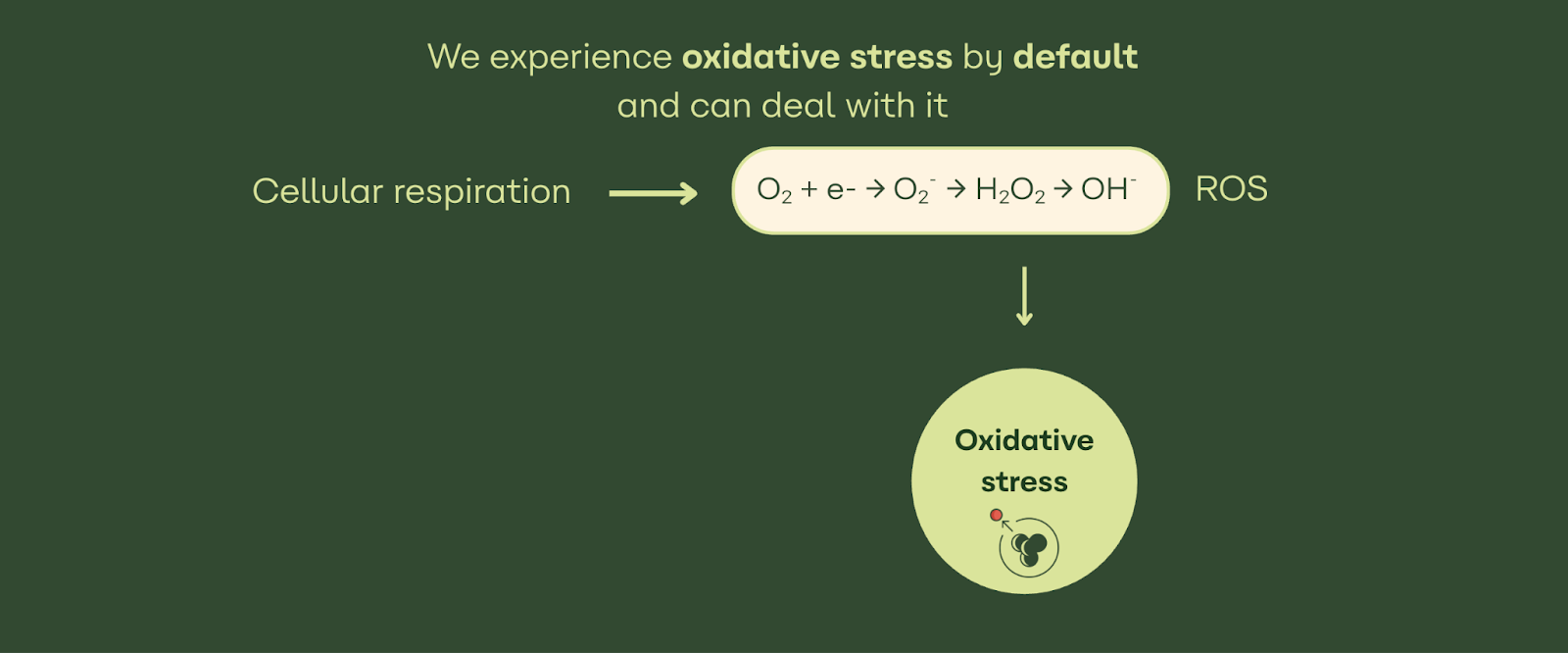

Inflammaging works through a molecular cascade that keeps cells in a state of stress. Pro-inflammatory transcription factors like NF-κB remain constantly active, driving the expression of cytokines and adhesion molecules. This chronic signaling damages DNA, alters epigenetic regulation, and promotes oxidative stress.

Over time, this not only accelerates telomere shortening but also reduces the efficiency of mitochondrial energy production. The result is a vicious cycle: damaged mitochondria produce more reactive oxygen species (ROS), which further trigger inflammation-a process astaxanthin has been shown to interrupt through both antioxidant and anti-inflammatory mechanisms (Park et al., 2010).

Epidemiological Evidence: Inflammaging's Role in Major Age-Related Diseases

Large-scale studies consistently link chronic inflammation with higher mortality risk. For example, high CRP levels are associated with a 1.5–2-fold increased risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes (Ridker et al., 2000). Similarly, elevated IL-6 predicts functional decline and mortality in older adults (Harris et al., 1999).

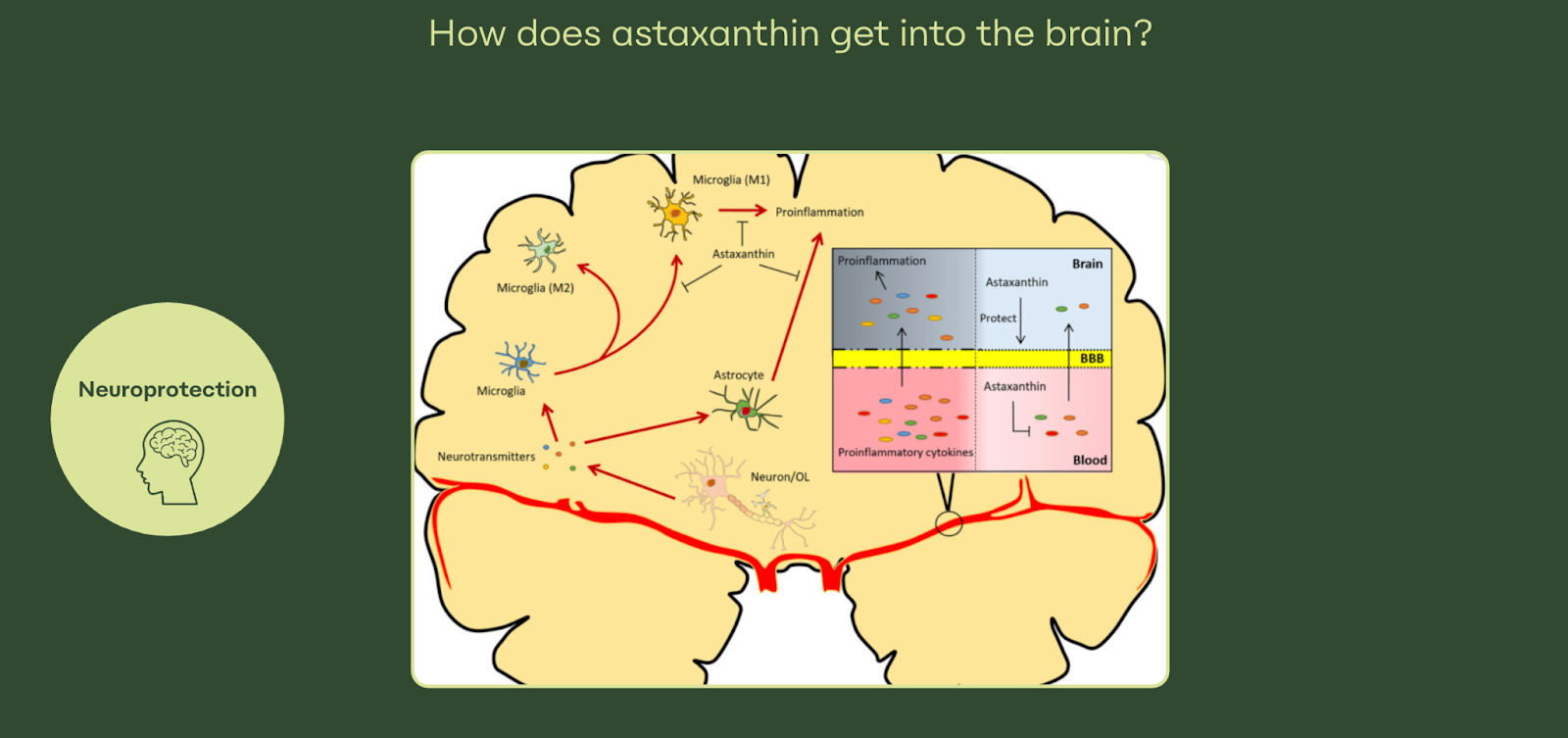

Neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer's disease also show clear connections to inflammaging, with microglial overactivation fueling progressive neuronal loss (Zhang, W. et al., 2023). These findings make it clear: inflammaging is not just a biomarker of aging-it's a driver of age-related disease burden. Learn more about how astaxanthin supports brain and cognitive health.

Zombie Cells: The Cellular Undead Fueling Inflammatory Aging

Perhaps the most fascinating-and sinister-contributors to inflammaging are senescent cells, often referred to as zombie cells. These are cells that have permanently stopped dividing but refuse to die. Instead, they remain metabolically active, secreting inflammatory molecules that damage their neighbors.

Zombie cells accumulate in tissues with age, especially under conditions of oxidative stress, obesity, and chronic disease. And their presence is increasingly seen as a major therapeutic target for longevity interventions.

Understanding Senescent Cells: From Cellular Guardians to Inflammatory Broadcasters

Initially, cellular senescence acts as a protective mechanism. When cells are damaged or at risk of turning cancerous, senescence halts their growth to prevent malignant transformation. But as these cells accumulate, their role shifts from protective guardians to inflammatory disruptors.

Instead of staying silent, senescent cells release a cocktail of pro-inflammatory factors, growth signals, and proteases that spread dysfunction throughout their environment. This is one of the key drivers of the inflammatory microenvironments seen in aging tissues (Campisi, 2013).

The SASP Factor: How Zombie Cells Create Inflammatory Neighborhoods

The Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP) describes the storm of molecules secreted by zombie cells. SASP includes cytokines like IL-6 and IL-1β, chemokines that attract immune cells, and enzymes that degrade the extracellular matrix.

Rather than resolving damage, SASP creates inflammatory neighborhoods-spreading dysfunction to healthy cells and accelerating tissue decline. In animal models, clearing senescent cells reduces systemic inflammation and restores tissue function, highlighting the central role of SASP in inflammaging (Xu et al., 2018).

Clinical Implications: Measuring Senescent Cell Burden in Aging Assessment

Measuring senescence in humans is complex, but several biomarkers are now emerging. p16^INK4a expression, senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity, and SASP cytokine profiles are among the most promising indicators of senescent cell burden (Wiley et al., 2017).

Clinical trials with senolytic drugs-compounds designed to selectively remove senescent cells-have shown early promise in reducing frailty and improving metabolic health in humans. For companies developing active ingredients, this underscores the need for compounds like astaxanthin, which may indirectly support healthy aging by reducing oxidative stress and dampening the inflammatory environment that fuels senescence. Explore the 13 most important research studies backing astaxanthin benefits.

The Inflammation-Disease Connection: Mapping the Pathways to Chronic Illness

The reach of inflammaging extends across nearly every chronic disease of aging. The biological link is clear: persistent low-grade inflammation damages tissues, disrupts metabolism, and accelerates cellular aging.

Cardiovascular Disease: How Inflammaging Attacks Your Heart and Arteries

In cardiovascular disease, inflammaging contributes to atherosclerosis-the buildup of plaques in arteries. Inflammatory cytokines activate endothelial cells, making them "sticky" for immune cells. Over time, this creates unstable plaques prone to rupture, leading to heart attacks or strokes. CRP and IL-6 are strong independent predictors of cardiovascular events, showing the critical role of inflammation in vascular decline (Ridker, 2016).

Neurodegeneration: When Brain Inflammation Leads to Cognitive Decline

In the brain, chronic inflammation drives microglial overactivation. Instead of protecting neurons, these immune cells start producing neurotoxic mediators, fueling diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's. Elevated inflammatory markers in midlife are associated with up to a 60% higher risk of dementia decades later (Walker et al., 2019). Discover how astaxanthin provides neuroprotective benefits for brain health.

Metabolic Dysfunction: The Inflammatory Roots of Diabetes and Obesity

Obesity itself is now recognized as an inflammatory state. Adipose tissue secretes pro-inflammatory adipokines, which interfere with insulin signaling and promote metabolic dysfunction. This explains why chronic inflammation is a causal driver of type 2 diabetes-not just a byproduct. Longitudinal studies show that individuals with higher baseline IL-6 and CRP have a significantly increased risk of developing insulin resistance and diabetes (Pradhan et al., 2001).

Astaxanthin: Nature's Most Potent Anti-Inflammatory and Longevity Compound

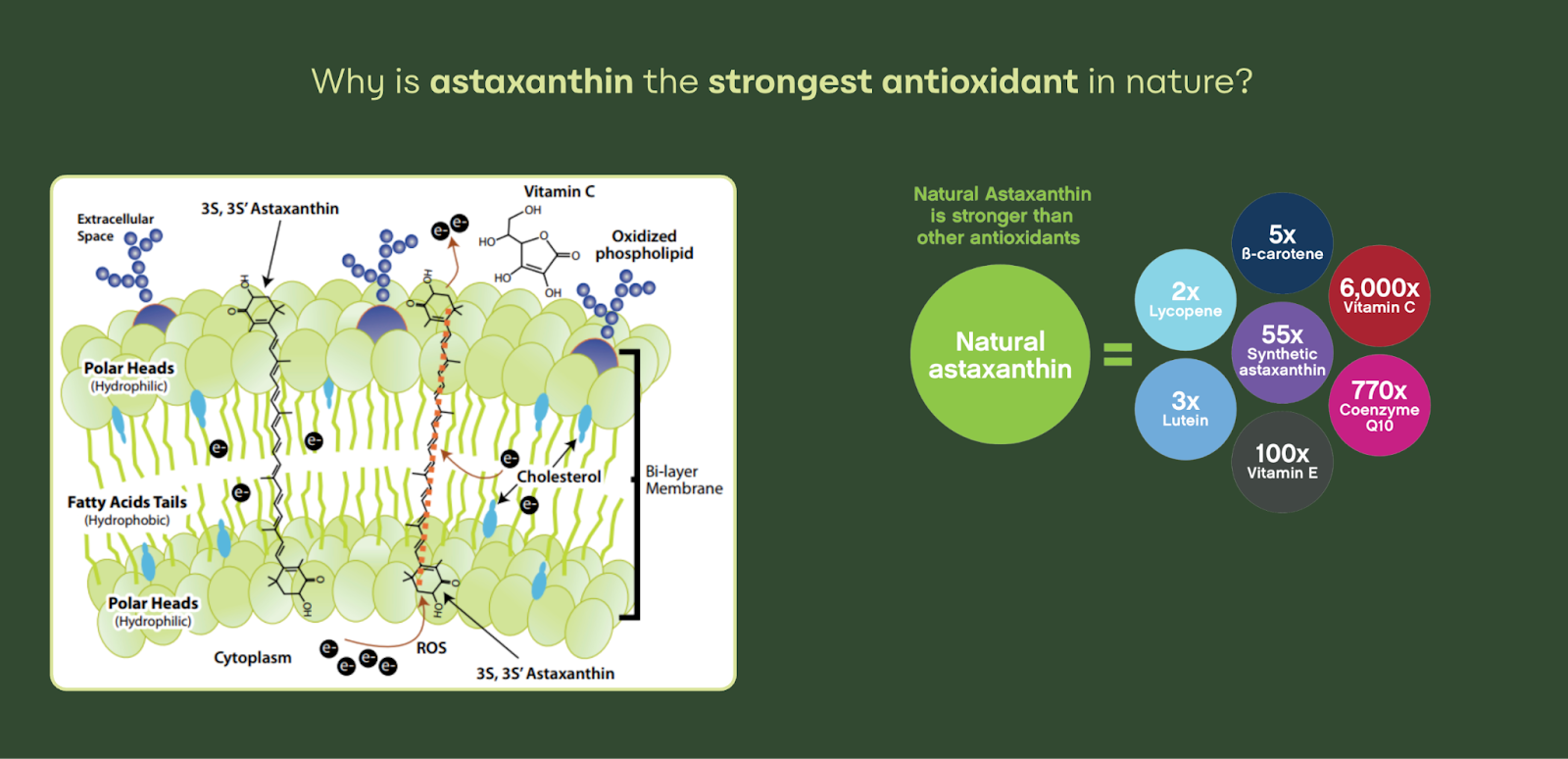

Astaxanthin isn't just another antioxidant-it's often called the "king of carotenoids" for good reason. Unlike many common antioxidants that only work in water or fat, astaxanthin is uniquely amphipathic, meaning it can span both environments. This rare property allows it to insert across cell membranes, protecting them inside and out from oxidative and inflammatory damage.

This dual-solubility characteristic makes astaxanthin a strategic active for targeting inflammaging. Its role extends beyond scavenging free radicals: it directly modulates inflammatory pathways, supports mitochondrial efficiency, protects DNA, and helps maintain cellular resilience. In fact, multiple studies have shown that astaxanthin's potency exceeds well-known antioxidants like vitamin E, beta-carotene, and coenzyme Q10 in several key assays (Nishida et al., 2007).

The Unique Molecular Structure: Why Astaxanthin Outperforms Other Antioxidants

The secret behind astaxanthin's superior performance lies in its molecular design. Unlike most antioxidants that operate in a single cellular compartment, astaxanthin acts as a bridge across membranes, neutralizing free radicals where they cause the most harm.

Chemical Architecture: The Xanthophyll Advantage Over Beta-Carotene and Vitamin E

Astaxanthin is a xanthophyll carotenoid with polar end groups containing hydroxyl and keto groups. These ends anchor into the polar surfaces of lipid bilayers, while the long conjugated polyene chain spans the hydrophobic membrane core.

By contrast, beta-carotene sits entirely within the lipid portion of the membrane, and vitamin E localizes to the membrane surface. This positioning makes astaxanthin uniquely suited to stabilize and protect entire membranes against oxidative stress (Ambati et al., 2014). This is also why formulators are increasingly choosing astaxanthin over alternatives like alpha-lipoic acid.

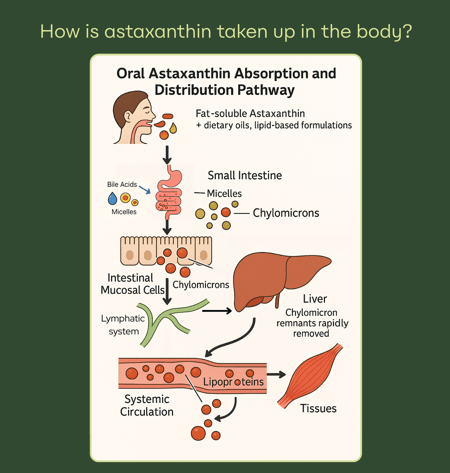

Bioavailability and Membrane Integration: How Structure Determines Function

Astaxanthin's lipophilicity ensures strong integration into phospholipid membranes. Once incorporated, it not only scavenges free radicals but also enhances membrane fluidity and integrity, helping cells withstand oxidative and inflammatory assaults.

Moreover, its bioavailability improves when taken with dietary fats, as shown in human studies where co-ingestion with lipids significantly boosted plasma astaxanthin levels (Mercke Odeberg et al., 2003). This is particularly relevant for supplement developers seeking optimal formulation strategies. Explore axabio's premium astaxanthin products designed for enhanced bioavailability.

Comparative Potency: ORAC Values and Real-World Antioxidant Performance

In oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) testing, astaxanthin consistently outperforms other carotenoids. For example, one study showed that astaxanthin was 10 times stronger than beta-carotene and 100 times stronger than alpha-tocopherol (vitamin E) in quenching singlet oxygen-a highly reactive oxidant implicated in aging (Higuera-Ciapara et al., 2006).

But beyond lab values, clinical research supports real-world outcomes: supplementation has been shown to reduce markers of oxidative stress, lower inflammation, and improve lipid peroxidation resistance in humans (Park et al., 2010). Learn more about astaxanthin's comprehensive health benefits.

Mechanisms of Anti-Inflammatory Action: How Astaxanthin Breaks the Inflammation Cycle

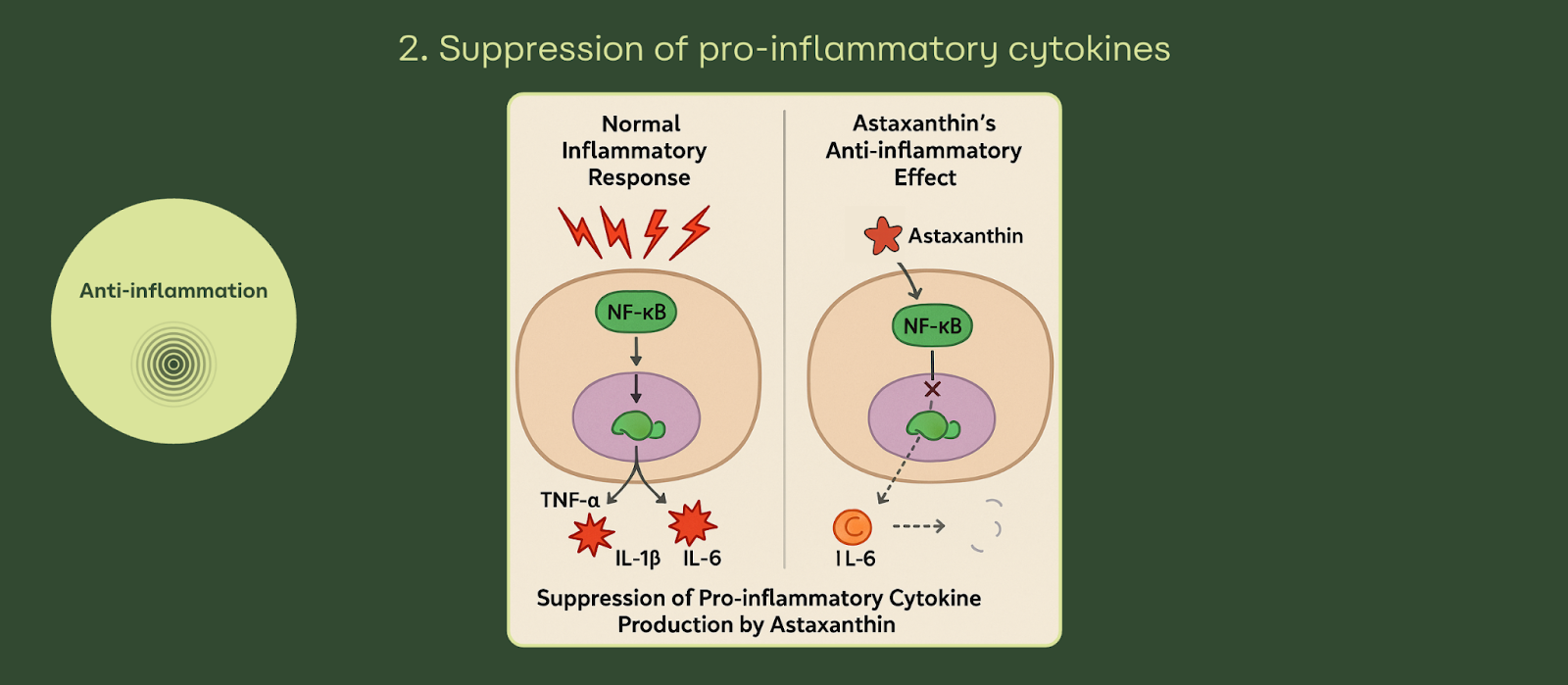

Astaxanthin doesn't just neutralize free radicals-it actively modulates inflammatory signaling pathways, cutting off inflammaging at its roots. This is critical because chronic inflammation isn't just about oxidative stress; it's about gene expression, immune signaling, and cellular stress responses.

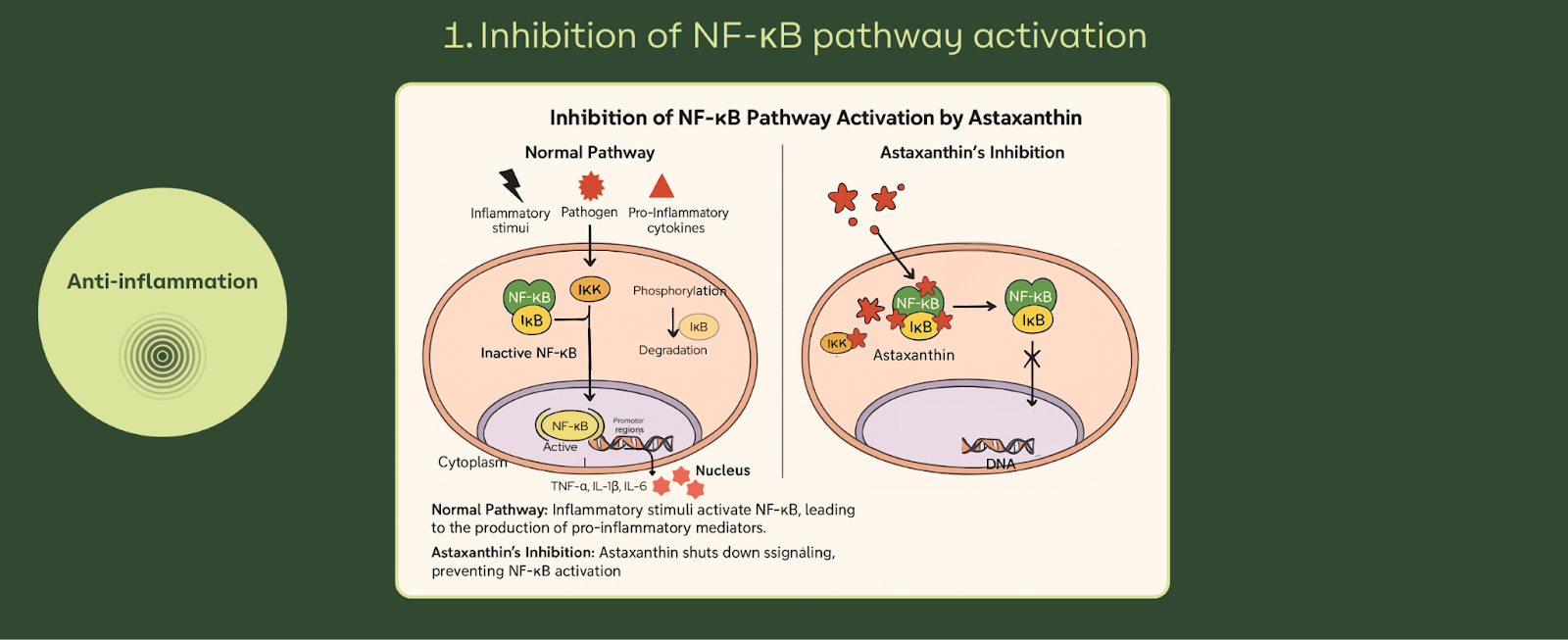

NF-κB Pathway Inhibition: Shutting Down Inflammatory Gene Expression

NF-κB is a transcription factor that acts like a master switch for inflammation, controlling the expression of cytokines, adhesion molecules, and enzymes like COX-2. In chronic disease, this switch is left permanently "on."

Astaxanthin has been shown to inhibit NF-κB activation, thereby downregulating pro-inflammatory gene expression. For instance, in macrophage models, astaxanthin reduced NF-κB nuclear translocation and decreased production of TNF-α and IL-1β (Lee et al., 2003). This mechanism is central to its role in combating inflammaging.

Cytokine Modulation: Balancing Pro- and Anti-Inflammatory Signaling

Inflammaging is marked by an imbalance between pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α) and anti-inflammatory mediators (IL-10). Clinical studies show that astaxanthin supplementation helps restore this balance.

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled human trial, 8 weeks of astaxanthin supplementation significantly lowered plasma CRP and IL-6 while enhancing immune cell function (Park et al., 2010). This suggests astaxanthin works as an immune balancer-not simply a suppressant-which is crucial for maintaining defense without collateral damage.

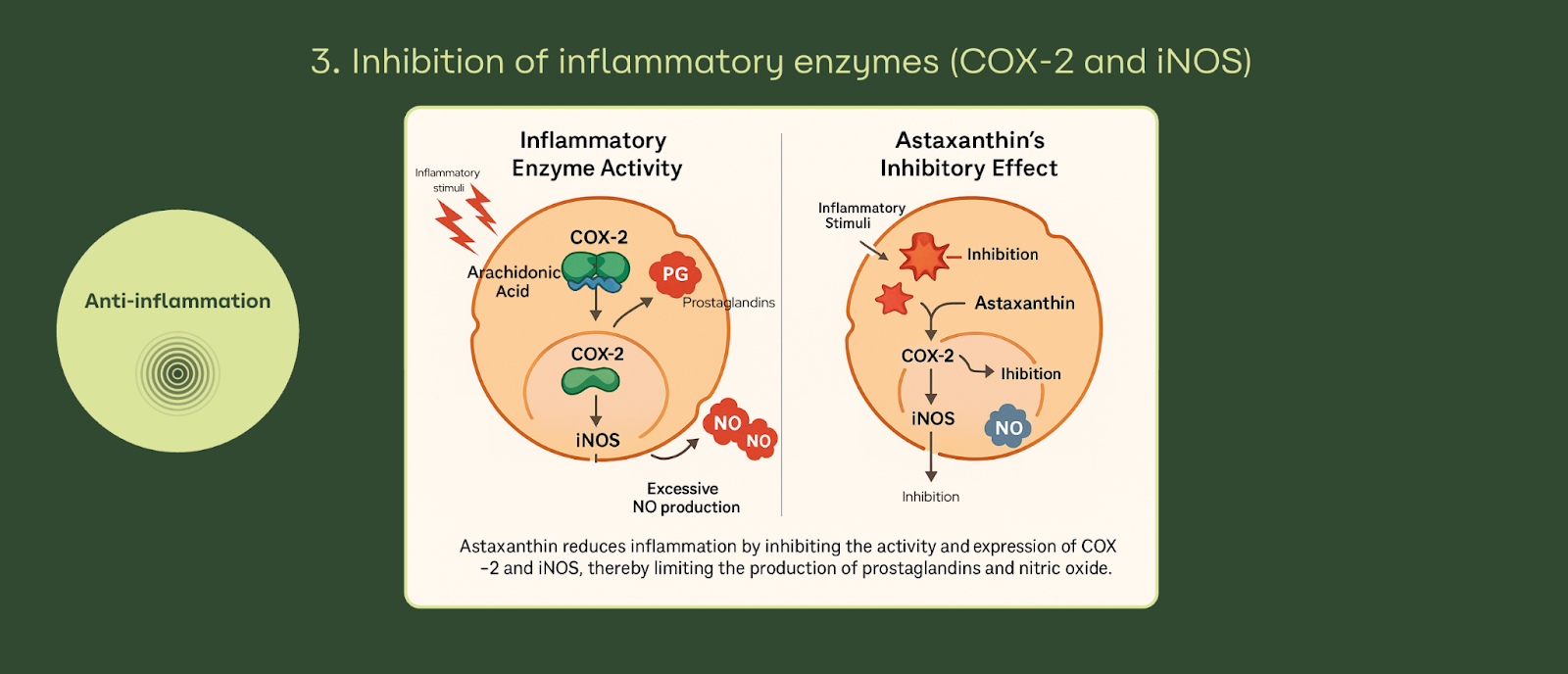

Nitric Oxide Regulation: Protecting Against Oxidative Stress Damage

Nitric oxide (NO) plays a dual role: in small amounts, it supports vascular health and immune signaling, but in excess, it contributes to oxidative stress and tissue damage.

Astaxanthin modulates NO production by inhibiting inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), reducing pathological NO release while preserving endothelial NO for vascular health. This dual action helps prevent oxidative damage in blood vessels, protecting against atherosclerosis and vascular inflammation (Naguib, 2000).

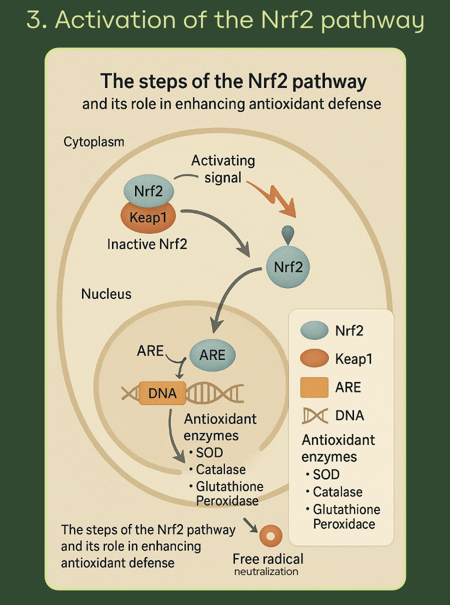

Cellular Protection and Longevity Pathways

The benefits of astaxanthin extend far beyond inflammation. It influences key cellular longevity mechanisms, making it a unique compound for extending healthspan-not just lifespan.

Mitochondrial Enhancement: Boosting Cellular Energy and Reducing Oxidative Stress

Mitochondria are both the powerhouse and the Achilles' heel of the cell. They generate ATP but also leak ROS as a byproduct. Chronic mitochondrial dysfunction is a central feature of inflammaging.

Astaxanthin localizes to mitochondrial membranes, where it improves respiratory chain efficiency and reduces ROS leakage. In animal studies, supplementation enhanced mitochondrial function and reduced oxidative stress in skeletal muscle, improving endurance and resilience (Aoi et al., 2008). This is why astaxanthin is increasingly popular among athletes seeking performance and recovery benefits.

Autophagy Activation: Supporting Cellular Cleanup and Regeneration

Autophagy is the cell's housekeeping system, recycling damaged proteins and organelles. With age, autophagy declines, contributing to protein aggregation and cellular dysfunction.

Astaxanthin has been shown to stimulate autophagy-related pathways, including upregulation of Beclin-1 and LC3-II proteins in neuronal and hepatic models (Zhang et al., 2015). By supporting autophagy, astaxanthin helps maintain cellular homeostasis and regenerative capacity.

Telomere Protection: Evidence for Chromosomal Integrity Preservation

Telomeres-the protective caps of chromosomes-shorten with every cell division and are highly sensitive to oxidative stress. Accelerated telomere shortening is directly linked to premature aging and increased disease risk.

In a clinical trial, astaxanthin supplementation was associated with reduced oxidative DNA damage and preservation of telomere length in immune cells (Nakagawa et al., 2011). This suggests astaxanthin may help maintain chromosomal stability, supporting healthier cellular aging trajectories.

Astaxanthin's Targeted Benefits for Age-Related Health Challenges

Astaxanthin shines when applied to the real-world problems aging brings: chronic stress and reduced vitality, gut barrier disruption, and cell-level protection beyond generic antioxidant effects. Below is the latest human and animal evidence, mechanistic insights, and pointers for using astaxanthin in products targeting these challenges.

Combating Stress and Enhancing Energy and Vitality

Chronic stress, especially when mediated via the HPA axis, pushes the body into a persistent inflammatory and oxidative load. Energy and vitality decline as mitochondria falter, cortisol stays elevated, and immune function degrades. Astaxanthin offers promising avenues to interrupt this cascade (Juszczyk et al., 2021).

HPA Axis Modulation: How Astaxanthin Helps Manage Chronic Stress Response

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis responds to perceived stress by releasing cortisol. If stress is prolonged, cortisol remains high; this not only dampens mood and immunity, it generates oxidative stress and damages tissues including in the brain.

Animal and in vitro work show astaxanthin can modulate HPA-axis activity. For example, in rodent models, astaxanthin reduces glucocorticoid-induced oxidative damage and dampens hyperactivation of stress pathways (Juszczyk et al., 2021). Human data are scarcer here, but preliminary evidence points toward reduced physiological stress markers with supplementation.

Cortisol Regulation: Clinical Evidence for Stress Hormone Balance

Direct human trials measuring cortisol and astaxanthin are limited. However, related endpoints like mood, heart rate, and endurance give signals consistent with stress reduction. In a double-blind study (8 weeks, 12 mg/day of natural astaxanthin from Haematococcus pluvialis) with 28 healthy adults, subjects taking astaxanthin showed improved mood state (reduced tension, fatigue, etc.) and lower average heart rate at submaximal exercise than placebo. These effects indirectly suggest improved stress regulation or lower systemic stress load (Talbott et al., 2019).

Mitochondrial Biogenesis: Boosting Cellular Energy Production for Enhanced Vitality

The decline in mitochondrial function with age and under stress is a core part of inflammaging. Astaxanthin helps here by preserving mitochondrial membrane potential under oxidative stress in neuronal models (Wang et al., 2022), and enhancing activity of antioxidant enzymes near mitochondria (Juszczyk et al., 2021).

Gut Health and the Inflammation-Microbiome Connection

The gut isn't just for digestion-it's a central interface where external insults, microbiota, immune cells, and barrier integrity meet. Disruption here ("leaky gut") contributes to systemic inflammation, metabolic dysfunction, and may feed back into neuroinflammation. Astaxanthin shows activity on multiple fronts of gut health.

Intestinal Barrier Protection: Preventing Leaky Gut and Systemic Inflammation

Animal studies suggest that astaxanthin helps preserve or restore barrier function. In DSS-induced colitis in mice, supplementation increased colon length, reduced disease activity scores, attenuated inflammatory markers, and mitigated epithelial barrier damage (Wang et al., 2022).

Another study in diabetic mice demonstrated that astaxanthin ameliorated kidney inflammation by modulating the gut-kidney axis, reducing oxidative stress in the kidney while improving gut microbiota composition and reducing markers of gut permeability (Ha et al., 2023).

Microbiome Modulation: Supporting Beneficial Bacterial Populations

Astaxanthin alters gut microbiota in ways associated with better metabolic and immune health. In rodent models, supplementation increased relative abundance of Lactobacillaceae and reduced taxa linked to inflammation. It also tended to increase short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which improve barrier function, immune modulation, and systemic inflammation (Wu et al., 2020).

Digestive Inflammation: Clinical Applications in IBD and IBS Management

Though robust human trials are still sparse, the animal colitis models strongly suggest that astaxanthin may be useful in inflammatory gut disorders. Reductions in cytokines like TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, along with reduced oxidative stress markers, point to a mechanism relevant for IBD (ulcerative colitis, Crohn's) or possibly IBS when inflammation is an underlying factor (Wang et al., 2022).

Advanced Cellular Protection: Beyond Basic Antioxidant Function

Astaxanthin offers protection at the DNA, protein, membrane, and cell quality control levels. For aging populations, cosmetic or supplement products that do more than neutralize radicals stand out-those that help maintain genomic integrity, reduce senescent cell burden, or prevent protein aggregation.

DNA Damage Prevention: Protecting Genetic Material from Oxidative Assault

In a human trial of young healthy women, supplementation with 2 mg/day astaxanthin for 8 weeks significantly reduced biomarkers of DNA damage and decreased CRP levels (Park et al., 2010). This highlights its potential to maintain genomic stability.

Protein Aggregation Inhibition: Preventing Age-Related Cellular Dysfunction

Protein misfolding and aggregation-as in neurodegenerative disorders-often result from oxidative stress and impaired proteostasis. Astaxanthin has shown in neural cell and animal models that it reduces aggregation, supports chaperone and proteasome function, and modulates AMPK/Nrf2 pathways that enhance cleanup systems (Wang et al., 2022).

Membrane Stabilization: Maintaining Cellular Integrity Under Stress

Astaxanthin integrates into cell and mitochondrial membranes, improving fluidity, reducing lipid peroxidation, and protecting against UVA, toxins, or metabolic byproducts. Stable membranes leak fewer signals that activate immune pathways, reducing inflammaging (Wang et al., 2022). This membrane protection is also why astaxanthin delivers exceptional skin benefits.

Clinical Evidence and Real-World Applications

Translating promising laboratory mechanisms into measurable human benefit is the essential test for any ingredient intended to combat inflammaging. For astaxanthin, the clinical landscape today is a mix of small, well-designed randomized trials, several systematic reviews/meta-analyses showing modest but consistent biomarker effects, and robust preclinical data (including lifespan and anti-senescence signals) that together justify targeted formulation programs for longevity and inflammaging applications.

Human Studies: Translating Laboratory Science to Clinical Outcomes

Human evidence for astaxanthin spans healthy volunteers, metabolic disease cohorts, and disease-specific trials (e.g., coronary artery disease). Across trials, endpoints commonly measured include oxidative stress markers (e.g., malondialdehyde, isoprostanes), inflammatory biomarkers (CRP, IL-6, TNF-α), immune function measures, and cardiometabolic parameters.

Results are not uniformly large, but two consistent themes appear: (1) astaxanthin reduces markers of lipid peroxidation and some inflammatory cytokines in specific populations, and (2) it displays an excellent safety and tolerability profile at typical supplement doses (2–12 mg/day). These findings are reinforced by pooled analyses that find small-to-moderate improvements in oxidative stress and, in some subgroups (notably people with metabolic dysfunction), IL-6 reduction and improvements in lipid oxidation markers (Ma et al., 2021). For a curated summary of the clinical evidence, access our white paper featuring 13 essential studies.

Randomized Controlled Trials: Inflammation Biomarker Improvements

Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials provide the highest-quality evidence we have so far. A foundational study randomized young healthy women to 0, 2, or 8 mg/day for 8 weeks and found a dose-dependent rise in plasma astaxanthin, reduced a DNA-damage biomarker, and lower CRP at 2 mg/day, alongside immune function improvements (natural killer activity, lymphoproliferation). Importantly, IL-6 and IFN-γ rose in the 8 mg group, showing that immune modulation may be dose- and context-dependent rather than uniformly suppressive (Park et al., 2010).

Meta-analyses pooling randomized trials report a modest but statistically meaningful reduction in lipid peroxidation (malondialdehyde) and, in people with type 2 diabetes, a reduction in IL-6. Effects on CRP and TNF-α are less consistent across the literature, which likely reflects differences in dose, duration, participant health status, and endpoints measured (Ma et al., 2021). A growing set of controlled trials in cardiometabolic and inflammatory conditions (e.g., coronary artery disease, heart failure protocols) is underway or recently published, reporting improvements in lipid parameters and some inflammation/oxidative markers at 8–12 mg/day over 4–12 weeks-again, signaling clinically relevant but not universally large effects (Heidari et al., 2023; Trials Journal, 2024).

Longitudinal Studies: Long-term Health Outcomes and Survival Signals

Human longitudinal evidence linking dietary astaxanthin intake to hard endpoints (e.g., mortality, dementia incidence) is limited. In contrast, preclinical longitudinal studies are stronger: recent work in genetically diverse mice fed astaxanthin showed increased median lifespan and improvements in age-related phenotypes, supporting a plausible translation to healthspan benefits if mechanisms translate to humans (Harrison et al., 2023). These animal data bolster mechanistic rationales (reduced oxidative damage, improved mitochondrial function, preserved tissue integrity), but they do not substitute for large, long-term human outcome trials.

Population Studies: Dietary Astaxanthin and Disease Prevention

Population-level epidemiology directly tying dietary astaxanthin to disease prevention is sparse because dietary databases seldom measure astaxanthin precisely, and its primary dietary sources (salmon, crustaceans, algae) are consumed as part of complex patterns. However, mechanistic and clinical signals align with broader epidemiological findings that higher carotenoid and seafood intake correlate with lower cardiometabolic and neurodegenerative risk-consistent with a contribution from astaxanthin among other nutrients. Reviews of cardiovascular studies highlight improved LDL oxidation lag time and potential lipid benefits as plausible pathways for disease prevention (Fassett & Coombes, 2012). Learn about the best astaxanthin-rich foods to incorporate into your diet.

Dosage, Timing, and Optimization Strategies

Clinical trials use widely varying doses (2–12 mg/day are most common; some disease studies use up to 20 mg/day for short periods). Evidence suggests:

Low-dose effects (≈2 mg/day): Immune modulation and reduction in acute phase protein (CRP) in healthy subjects over ~8 weeks (Park et al., 2010).

Mid-range doses (6–12 mg/day): Common in athletic, metabolic, and cardiometabolic trials; associated with reductions in lipid peroxidation and improvements in selected inflammation or lipid parameters (Ma et al., 2021; Heidari et al., 2023).

Higher short-term doses (≥12–20 mg/day): Used in disease trials (e.g., heart failure, CAD protocols) to probe stronger metabolic or endothelial outcomes; safety data remain reassuring but require monitoring in medically complex populations (Trials Journal, 2024).

Formulation and bioavailability: Astaxanthin is lipophilic, so co-administration with dietary fat or lipid-based formulations (oil suspensions, micellized or microencapsulated forms) substantially improves plasma uptake; evidence supports choosing carriers that favor membrane delivery to maximize mitochondrial and cellular effects (Park et al., 2010). Explore axabio's range of bioavailable astaxanthin formats including oleoresins and softgels.

Senescence (zombie cells): Direct human evidence that astaxanthin reduces senescent cell burden (senolytic effect) is not established. However, preclinical and cellular studies show astaxanthin protects against stress-induced senescence (e.g., PM2.5-induced keratinocyte senescence via NRF2 signaling) and reduces SASP-related inflammation in models-mechanistic data that support designing clinical endpoints related to senescence biology (SASP cytokines, p16^INK4a expression, functional frailty scores) in future trials rather than claiming senolytic action today (Zhen et al., 2024; Harrison et al., 2023).

Practical Implementation: Integrating Astaxanthin into Your Longevity Protocol

Astaxanthin's strength lies in its versatility. While it offers clear anti-inflammatory and antioxidant benefits on a molecular level, those advantages only translate into tangible health outcomes when it is integrated thoughtfully into a daily regimen. The key is to balance natural sourcing, supplement innovation, and lifestyle synergies while enabling users to measure progress with clear biomarkers.

Natural Sources vs. Supplementation: Making Informed Choices

Astaxanthin can be obtained from dietary sources or high-purity supplements. Both have their advantages, but bioavailability, consistency, and concentration differ significantly.

Dietary Sources: Maximizing Astaxanthin from Salmon, Shrimp, and Algae

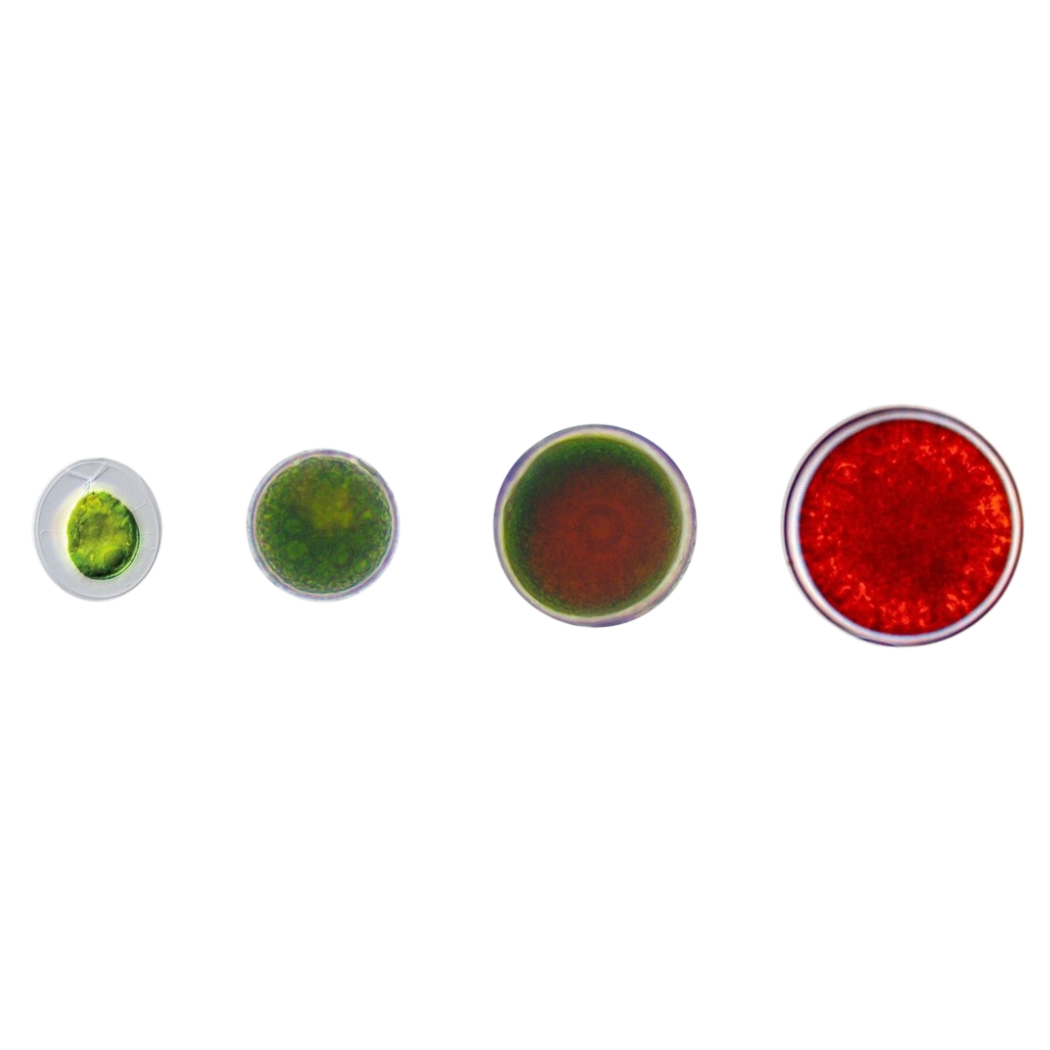

Wild salmon, krill, shrimp, lobster, and red trout are the most common natural sources of astaxanthin in the diet. For example, wild sockeye salmon can contain up to 26–38 mg/kg of astaxanthin in muscle tissue, meaning a standard serving (~150 g) provides only 4–6 mg-enough to match the lower end of supplement dosages (Kolniak-Ostek et al., 2021). However, dietary intake varies considerably depending on seafood type, preparation, and regional diet patterns. Microalgae (Haematococcus pluvialis) remains the richest natural source, and it is the cornerstone of most supplement formulations because of its concentrated yield and controlled cultivation potential.

Supplement Quality Assessment: Identifying High-Quality Astaxanthin Products

Supplements offer controlled and reproducible dosing, critical for both clinical efficacy and regulatory claims. However, quality varies widely. Key parameters to assess include:

Source verification: Is the astaxanthin extracted from Haematococcus pluvialis (gold standard) or from lower-quality sources?

Stability and purity: Natural astaxanthin is prone to oxidation; formulations must ensure protection through encapsulation or antioxidant blends.

Bioavailability: Lipid-based delivery systems (e.g., oil suspensions, microencapsulation) enhance absorption.

Certification: Look for third-party testing for purity, heavy metals, and contaminants.

For formulators, these considerations determine not just efficacy but also product differentiation in competitive markets. axabio's vertical bioreactor technology offers unmatched purity and stability while maintaining eco-responsibility-a value increasingly important to both consumers and regulators.

Synthetic vs. Natural: Understanding the Differences in Efficacy and Safety

Synthetic astaxanthin, produced from petrochemicals, is approved only for aquaculture feed-not human consumption-in most markets. Its isomer profile differs from natural astaxanthin, which typically contains both all-trans and 13-cis forms that are critical for biological activity. Studies indicate that natural astaxanthin has superior antioxidant potency and safety in humans compared to its synthetic counterpart (Ambati et al., 2014). For longevity-focused products, the choice is clear: natural astaxanthin delivers both efficacy and clean-label appeal. Download our comprehensive white paper on natural vs. synthetic astaxanthin for detailed scientific comparisons.

Lifestyle Synergies: Amplifying Astaxanthin's Benefits

Astaxanthin is not a magic bullet. Its effects are magnified when combined with lifestyle interventions that also regulate inflammation and oxidative stress.

Exercise Integration: How Physical Activity Enhances Anti-inflammatory Effects

Moderate, regular exercise is one of the most powerful anti-inflammatory interventions. It activates antioxidant defense pathways (e.g., NRF2), increases mitochondrial biogenesis, and reduces systemic CRP levels (Gleeson et al., 2011). Astaxanthin can complement this by protecting mitochondria from exercise-induced oxidative stress, improving endurance, and aiding recovery. Studies in athletes show supplementation reduces lipid peroxidation and muscle damage markers post-exercise (Earnest et al., 2011). For product positioning, this makes astaxanthin a strong fit for performance-longevity formulations.

Sleep Optimization: The Circadian Rhythm Connection to Inflammation

Poor sleep quality is tightly linked to elevated inflammatory markers, including IL-6 and CRP. Circadian rhythm disruption accelerates inflammaging processes and mitochondrial decline (Irwin, 2019). Astaxanthin, with its role in protecting neuronal tissue and supporting mitochondrial efficiency, may help buffer the oxidative stress associated with sleep deprivation. Combining supplementation with sleep hygiene interventions (consistent bedtime, limiting blue light, melatonin-friendly routines) provides synergistic protection.

Stress Management: Complementary Approaches for Maximum Longevity Benefits

Chronic psychological stress drives cortisol overproduction, suppresses immune resilience, and sustains low-grade inflammation. Stress also accelerates the accumulation of senescent "zombie cells," which fuel SASP-mediated inflammaging (Faget et al., 2019). Astaxanthin has been shown to modulate HPA axis activity and reduce markers of oxidative stress linked to chronic stress exposure. Pairing supplementation with mindfulness, breathing techniques, and adaptogenic compounds (e.g., ashwagandha, L-theanine) amplifies the resilience-building effects.

Monitoring Progress: Biomarkers and Assessment Tools

Integrating astaxanthin into a protocol is only half the story; tracking its effectiveness is essential, especially in R&D or clinical applications.

Inflammatory Markers: Which Tests to Track Your Progress

Routine biomarkers such as high-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP), IL-6, and TNF-α offer reliable windows into systemic inflammation. Reductions in these markers after 8–12 weeks of supplementation have been documented in metabolic and cardiovascular cohorts (Ambati et al., 2014). In product trials, including these endpoints helps validate claims and regulatory compliance.

Functional Health Assessments: Beyond Laboratory Values

Functional tests-such as VO₂ max (for mitochondrial performance), endothelial function assessments (FMD testing), or cognitive performance tasks-offer insight into how reduced inflammation translates into real-world healthspan improvements. Athlete studies, for example, have shown faster recovery and reduced oxidative stress markers with astaxanthin, suggesting performance outcomes are valuable secondary measures (Earnest et al., 2011).

Long-term Health Monitoring: Creating Your Personal Longevity Dashboard

For long-term implementation, a "longevity dashboard" combining blood biomarkers (CRP, fasting glucose, lipid profile), functional measures (strength, endurance, cognition), and advanced markers (DNA methylation clocks, telomere length) provides a more complete picture. While astaxanthin alone will not halt aging, its integration into a broader protocol-including diet, exercise, stress resilience, and sleep-supports measurable improvements in cellular health and inflammaging control.

Ready to Formulate with Premium Natural Astaxanthin?

For brands and formulators looking to develop next-generation longevity, anti-aging, or wellness products, axabio offers the purest, most stable natural astaxanthin on the market. Produced in Belgium using patented vertical bioreactor technology and supercritical CO₂ extraction, our astaxanthin delivers:

- Superior 3S,3'S stereoisomer profile for maximum bioactivity

- Exceptional stability and shelf life

- Sustainable, eco-responsible production

- Expert formulation support

Explore our product range or contact our team to discuss your specific formulation needs.

FAQ

Frequently asked questions about Astaxanthin and Inflammaging-

Inflammaging is chronic, low-grade inflammation that develops as we age. Unlike acute inflammation (which heals injuries), inflammaging is a persistent, smoldering process that accelerates cellular aging and drives chronic diseases like heart disease, diabetes, Alzheimer's, and cancer. It's now recognized as one of the strongest predictors of biological age and healthspan decline. Addressing inflammaging early can significantly impact how well you age.

-

Astaxanthin combats inflammaging through multiple mechanisms. It inhibits NF-κB—the master switch for inflammatory gene expression—reducing production of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-6 and TNF-α. It also neutralizes free radicals that trigger inflammatory cascades, protects mitochondria from oxidative damage, and helps maintain cellular integrity. Unlike single-action antioxidants, astaxanthin works across both water and fat-soluble environments, providing comprehensive cellular protection. Learn more about astaxanthin's extraordinary antioxidant properties.

-

Astaxanthin's unique molecular structure allows it to span entire cell membranes, protecting both the inside and outside simultaneously. It's up to 6,000 times more potent than vitamin C and 550 times stronger than vitamin E in neutralizing singlet oxygen. Unlike vitamins C and E or beta-carotene, astaxanthin never becomes a pro-oxidant—it remains protective even after neutralizing free radicals. This makes it exceptionally effective for long-term anti-inflammatory support. Discover why formulators are switching from alpha-lipoic acid to astaxanthin.

-

Zombie cells (senescent cells) are damaged cells that stop dividing but refuse to die. Instead, they release inflammatory molecules called SASP (Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype) that spread dysfunction to healthy neighboring cells. While astaxanthin isn't classified as a senolytic (it doesn't directly kill zombie cells), it reduces the oxidative stress that triggers senescence and dampens the inflammatory environment that zombie cells create—essentially limiting their harmful impact.

-

Clinical studies show benefits across a range of doses:

- 2-4 mg/day: Supports immune function and reduces CRP in healthy individuals

- 6-8 mg/day: Most common dose for general anti-inflammatory and antioxidant support

- 8-12 mg/day: Used in cardiovascular and metabolic studies for stronger effects

- 12-20 mg/day: Higher doses used in disease-specific trials (consult healthcare provider)

For most people targeting inflammaging, 6-12 mg/day of natural astaxanthin taken with a fat-containing meal provides optimal benefits.

-

Clinical trials typically show measurable changes in inflammatory biomarkers (like CRP and IL-6) within 4-8 weeks of consistent supplementation. Some oxidative stress markers improve even faster. However, the full benefits for inflammaging—including cellular protection and longevity pathways—likely accumulate over months of regular use. Consistency matters more than high doses.

-

It's challenging. Wild sockeye salmon—one of the richest food sources—contains about 4-6 mg per 150g serving. You'd need to eat salmon daily to match supplement doses used in clinical research. Other sources like shrimp, lobster, and trout contain less. For therapeutic anti-inflammatory benefits, supplements provide more reliable and concentrated dosing. That said, including astaxanthin-rich foods in your diet offers complementary nutrients and supports overall health.

-

Key biomarkers to monitor include:

- hs-CRP (high-sensitivity C-reactive protein): General inflammation marker

- IL-6 and TNF-α: Pro-inflammatory cytokines

- MDA (malondialdehyde): Lipid peroxidation/oxidative stress marker

- 8-OHdG: DNA oxidative damage marker

- Fasting glucose and HbA1c: Metabolic inflammation indicators

- Lipid panel (especially oxidized LDL): Cardiovascular inflammation

A baseline test before starting supplementation, followed by retesting at 8-12 weeks, provides meaningful data on individual response.

-

Each has unique strengths:

- Astaxanthin: Exceptional membrane protection, crosses blood-brain barrier, never pro-oxidant, broad antioxidant + anti-inflammatory action

- Curcumin: Strong NF-κB inhibition but poor bioavailability without special formulations

- Omega-3s: Essential for resolving inflammation, support cell membrane fluidity

These compounds work through complementary mechanisms and can be combined. Astaxanthin's advantage is its comprehensive cellular protection—it works in both aqueous and lipid environments simultaneously, something neither curcumin nor omega-3s can do alone.

-

axabio produces natural astaxanthin from Haematococcus pluvialis microalgae cultivated in Belgium using patented vertical bioreactor technology. This controlled indoor system ensures:

- No contamination from environmental pollutants

- Consistent, high-purity product

- Optimal 3S,3'S stereoisomer profile

- Sustainable production with minimal environmental footprint

- Supercritical CO₂ extraction (solvent-free)

This sets axabio apart from open-pond cultivation methods that can introduce impurities and inconsistencies.

References

- Ambati, R. R., Phang, S. M., Ravi, S., & Aswathanarayana, R. G. (2014). Astaxanthin: Sources, extraction, stability, biological activities and its commercial applications-A review. Marine Drugs, 12(1), 128–152. https://doi.org/10.3390/md12010128

- Aoi, W., Naito, Y., Takanami, Y., Ishii, T., Kawai, Y., Akagiri, S., ... & Yoshikawa, T. (2008). Astaxanthin improves muscle lipid metabolism in exercise via inhibitory effect of oxidative CPT I modification. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 366(4), 892–897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.019

- Campisi, J. (2013). Aging, cellular senescence, and cancer. Annual Review of Physiology, 75, 685–705. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183653

- Earnest, C. P., Lupo, M., White, K. M., & Church, T. S. (2011). Effect of astaxanthin supplementation on muscle damage and oxidative stress markers in elite athletes. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 32(12), 882–888. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1280778

- Faget, D. V., Ren, Q., & Stewart, S. A. (2019). Unmasking senescence: Context-dependent effects of SASP in cancer and aging. Cell, 179(3), 562–583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2019.09.052

- Fassett, R. G., & Coombes, J. S. (2012). Astaxanthin in cardiovascular health and disease. Molecules, 17(2), 2030–2048. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules17022030

- Ferrucci, L., & Fabbri, E. (2018). Inflammageing: Chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nature Reviews Cardiology, 15(9), 505–522. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-018-0064-2

- Franceschi, C., Garagnani, P., Parini, P., Giuliani, C., & Santoro, A. (2018). Inflammaging: A new immune–metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 14(10), 576–590. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-018-0059-4

- Fulop, T., Witkowski, J. M., Olivieri, F., & Larbi, A. (2017). The integration of inflammaging in age-related diseases. Seminars in Immunology, 40, 17–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smim.2017.12.004

- Gleeson, M., Bishop, N. C., Stensel, D. J., Lindley, M. R., Mastana, S. S., & Nimmo, M. A. (2011). The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: Mechanisms and implications for the prevention and treatment of disease. Nature Reviews Immunology, 11(9), 607–615. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3041

- Ha, M., et al. (2023). Dietary AST supplementation could protect kidneys against inflammation and oxidative stress by adjusting the gut-kidney axis in diabetic mice. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. https://doi.org/10.1024/0300-9831/a000786

- Harris, T. B., Ferrucci, L., Tracy, R. P., Corti, M. C., Wacholder, S., Ettinger, W. H., ... & Wallace, R. (1999). Associations of elevated interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein levels with mortality in the elderly. American Journal of Medicine, 106(5), 506–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00066-2

- Harrison, D. E., Strong, R., Miller, R. A., Nadon, N. L., Perez, V. I., ... & Richardson, A. (2023). Astaxanthin extends lifespan and healthspan in genetically diverse mice. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.21.533671

- Heidari, M., Chaboksafar, Z., Alizadeh, M., Sohrabi, M. R., & Kheirouri, S. (2023). Effects of astaxanthin supplementation on selected metabolic parameters, anthropometric indices, Sirtuin1 and TNF-α levels in patients with coronary artery disease: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN, 55, 428–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnesp.2023.06.016

- Higuera-Ciapara, I., Félix-Valenzuela, L., & Goycoolea, F. M. (2006). Astaxanthin: A review of its chemistry and applications. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 46(2), 185–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408690590957188

- Irwin, M. R. (2019). Sleep and inflammation: Partners in sickness and in health. Nature Reviews Immunology, 19(11), 702–715. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-019-0190-z

- Juszczyk, G., Mikulska, J., Kasperek, K., Pietrzak, D., Mrozek, W., & Herbet, M. (2021). Chronic stress and oxidative stress as common factors of the pathogenesis of depression and Alzheimer's disease: The role of antioxidants in prevention and treatment. Antioxidants, 10(9), 1439. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10091439

- Kolniak-Ostek, J., Kaczmarek, A., Płóciennik, M., & Ostrowska-Ligęza, E. (2021). Astaxanthin-Sources, extraction methods, stability, biological activity and its potential applications in the food industry. Foods, 10(6), 1101. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10061101

- Lee, S. J., Bai, S. K., Lee, K. S., Namkoong, S., Na, H. J., Ha, K. S., ... & Kim, Y. M. (2003). Astaxanthin inhibits nitric oxide production and inflammatory gene expression by suppressing IκB kinase-dependent NF-κB activation. Molecular Cells, 16(1), 97–105. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14503865/

- Ma, B., Lu, J., Kang, T., Zhu, M., Xiong, K., & Wang, J. (2021). Astaxanthin supplementation mildly reduced oxidative stress and inflammation biomarkers: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrition Research, 99, 40–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2021.09.005

- Mercke Odeberg, J., Lignell, Å., Pettersson, A., & Höglund, P. (2003). Oral bioavailability of the antioxidant astaxanthin in humans is enhanced by incorporation of lipid-based formulations. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 19(4), 299–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0928-0987(03)00080-8

- Naguib, Y. M. (2000). Antioxidant activities of astaxanthin and related carotenoids. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 48(4), 1150–1154. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf991106k

- Nakagawa, K., Kiko, T., Miyazawa, T., Carpentero Burdeos, G., Kimura, F., Satoh, A., & Miyazawa, T. (2011). Antioxidant effect of astaxanthin on phospholipid peroxidation in human erythrocytes. British Journal of Nutrition, 105(11), 1563–1571. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114510005398

- Nishida, Y., Yamashita, E., & Miki, W. (2007). Quenching activities of common hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants against singlet oxygen using chemiluminescence detection system. Carotenoid Science, 11, 16–20. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/913017

- Park, J. S., Chyun, J. H., Kim, Y. K., Line, L. L., & Chew, B. P. (2010). Astaxanthin decreased oxidative stress and inflammation and enhanced immune response in humans. Nutrition & Metabolism, 7, 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-7-18

- Pradhan, A. D., Manson, J. E., Rifai, N., Buring, J. E., & Ridker, P. M. (2001). C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA, 286(3), 327–334. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.286.3.327

- Ridker, P. M. (2016). From C-Reactive Protein to Interleukin-6 to Interleukin-1: Moving upstream to identify novel targets for atheroprotection. Circulation Research, 118(1), 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306656

- Ridker, P. M., Hennekens, C. H., Buring, J. E., & Rifai, N. (2000). C-reactive protein and other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in women. New England Journal of Medicine, 342(12), 836–843. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200003233421202

- Talbott, S. M., Talbott, J. A., & Pugh, M. (2019). Effect of astaxanthin supplementation on psychophysiological heart-brain axis. Functional Foods in Health and Disease, 9(8), 555–571. https://ffhdj.com/index.php/ffhd/article/view/636

- Trials Journal. (2024). The effect of astaxanthin supplementation on inflammatory markers, oxidative stress indices, lipid profile, and endothelial function in heart failure subjects: Study protocol. Trials, 25(1), 518. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-024-08339-8

- Walker, K. A., Ficek, B. N., & Westbrook, R. (2019). Understanding the role of systemic inflammation in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiology of Aging, 72, 69–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.08.020

- Wang, S., et al. (2022). The putative role of astaxanthin in neuroinflammation by inhibiting oxidative stress. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 13, 916653. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.916653

- Wiley, C. D., Velarde, M. C., Lecot, P., Liu, S., Sarnoski, E. A., Freund, A., ... & Campisi, J. (2017). Mitochondrial dysfunction induces senescence with a distinct secretory phenotype. Cell Metabolism, 23(2), 303–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2015.11.011

- Wu, L., et al. (2020). Astaxanthin-shifted gut microbiota is associated with alteration of lipid metabolism in obese LPS-treated mice. Frontiers in Nutrition, 7, 586002. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2020.586002

- Xu, M., Pirtskhalava, T., Farr, J. N., Weigand, B. M., Palmer, A. K., Weivoda, M. M., ... & Kirkland, J. L. (2018). Senolytics improve physical function and increase lifespan in old age. Nature Medicine, 24(8), 1246–1256. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0092-9

- Zhang, L., Wang, H., Fan, Y., Gao, Y., Li, X., Hu, Z., ... & He, J. (2015). Dietary astaxanthin protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced cognitive impairment and neuroinflammation via the Nrf2 pathway. Marine Drugs, 13(9), 5975–5991. https://doi.org/10.3390/md13095975

- Zhang, W., Xiao, D., Mao, Q., & Xia, H. (2023). Role of neuroinflammation in neurodegeneration development. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-023-01486-5

- Zhen, A. X., Kim, J. H., Lee, S., Kim, H. S., Cho, S. C., & Kim, J. (2024). Protective effects of astaxanthin on PM2.5-induced senescence in HaCaT keratinocytes via NRF2 signaling. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(6), 17106. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms250617106